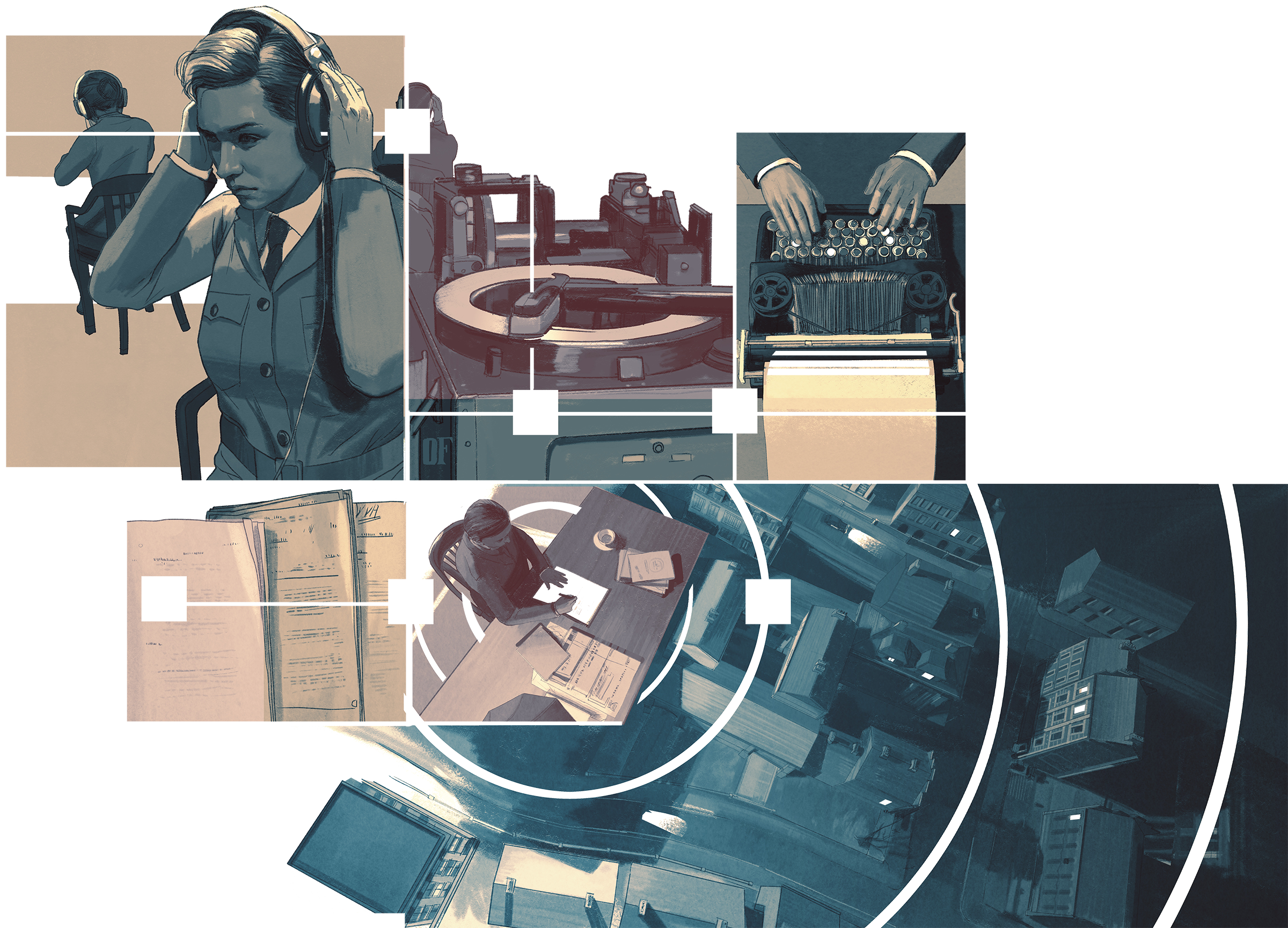

In the winter of 1939/1940 and under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Kendrick at MI-19, Trent Park house and grounds were transformed into a state-of-the art surveillance centre. Interrogation blocks and administrative offices were quickly thrown up in front of Sassoon’s mansion, which was itself adapted and installed with a complex network of miniaturised bugging devices hidden in every corner – in walls and skirtings, light fittings, plant pots, window ledges, the billiard table, even the garden benches.

How it Worked

The Agents

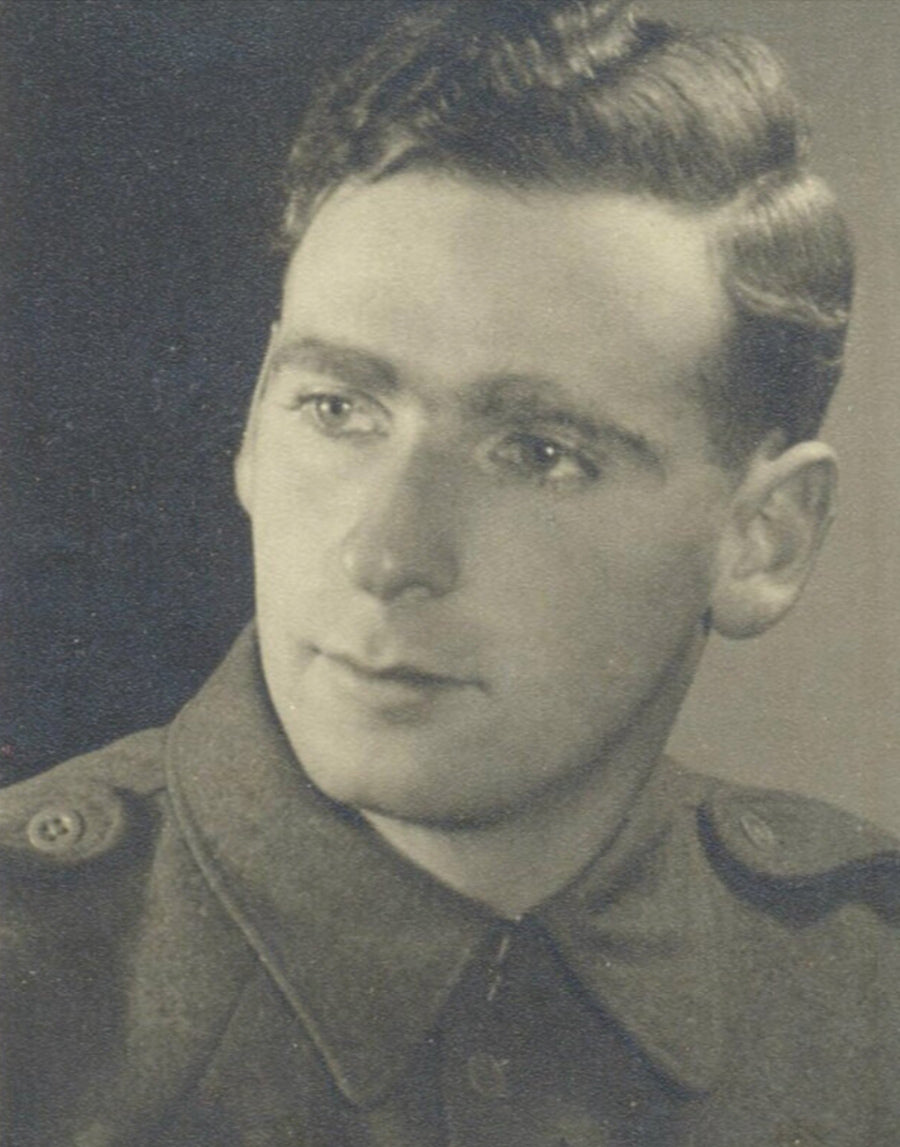

Eric Mark

Eric Mark’s story is typical of the recruited German émigré Kendrick appointed to the role of secret listeners at Trent Park. Born Erich Meyer in Magdeburg, Germany in 1922, his parents sent him to Britain in January 1935 to escape Nazi persecution. During the war, Eric joined the Pioneer Corps, and transferred to the Intelligence Corps in March 1944. He was then posted to Trent Park to take up secret listening duties.

Eric’s parents were sent to Treblinka concentration camp and did not survive.

After the war, Eric continued his education that had been halted by the war, studying for a degree at the London School of Economics. In 1947 he met Miriam, a Polish refugee, and the two were married in 1951. He began working for Shell International and was head of the European Commission’s directorate of transport until his retirement in 1987. He died in November 2020.

Ernst Lederer

Ernst Lederer was born in Teplitz, in the Sudetenland, in 1892. He enlisted to fight for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1914 and spent the First World War in the trenches alongside German and Italian soldiers.

After the war, Ernst married Margarette, with whom he had two children, and resumed his furniture business in Czechoslovakia. In 1939 under the shadow of war once more, Ernst made plans to leave Czechoslovakia, sending his son to school in England in 1938, before arriving himself in 1939. Then his wife and daughter arrived together on one of the last trains out.

While many German-speaking refugees were interned, Ernst Lederer was recruited by the Intelligence Corps and posted to Trent Park. He operated as a Stool Pigeon, tasked with mingling amongst the German generals to manipulate their conversations and tease out essential information. His affable personality may have come in useful when extracting information from the incarcerated generals. He was asked to assess their characters and interview them personally, and the generals were encouraged by these ‘stool pigeons’ to speak freely about the war.

Ernst’s work was vital in working out who the German prisoners were, where they fitted into the Nazi hierarchy and what intelligence they could be encouraged to give up. This not only gave an indication into attitudes towards Hitler, but also crucial information on weapons, tactics, and vital evidence into the Holocaust.

Catherine Townshend Jestin

During the Second World War women played a vital role in intelligence operations. One of Kendrick’s recruits to ‘Cockfosters Camp’, as Trent Park was known, was a young woman named Catherine Townshend. Born in London in 1920, Catherine was fiercely intelligent with a gift for languages, having studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, and then at Munich University, where she perfected her German.

At the outbreak of World War II, Catherine joined the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry as a driver and orderly. In January 1942 she was told to report to the War Office for a meeting, and following interview was transferred to British intelligence, rising to the rank of Captain for MI19, the Intelligence Corps.

In 1944 Catherine married Heimwarth Jestin, a Lieutenant Colonel in US intelligence working as an interrogator at Trent Park. After the war the couple relocated to the U.S. to settle and raise a family in the town of Farmington, Connecticut. She spent the rest of her working life as a librarian, and a few years before her death in 2004, she published a memoir, entitled ‘A War Bride’s Story: An Autobiography’.

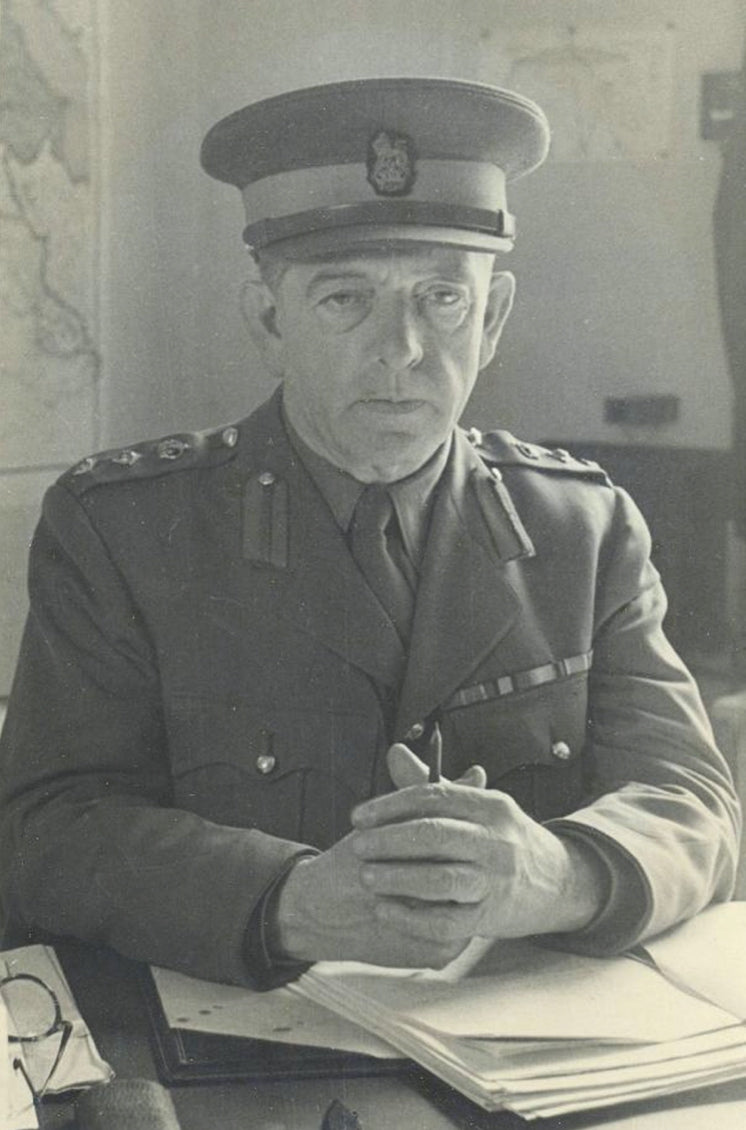

Thomas Kendrick

By early 1943 the secret listeners at Trent Park had documented many thousands of conversations, but Kendrick was acutely aware of an urgent need to recruit more secret listeners to deal with the increased intake of POWs following British victories in North Africa. An added problem was the complex technical language and numerous German dialects which were proving challenging for the first cohort of secret listeners, most of whom were British-born operatives chosen for their fluency in German.

Kendrick needed to find native German speakers for secret listening and found them in the form of German refugees serving in the British army’s Pioneer Corps. About 100 new listeners were drafted, almost all of them German-Jewish émigrés who had arrived in Britain fleeing Nazi persecution. As native German speakers, they were able to understand every informal word and utterance eavesdropped from the basement M Rooms.

Secret listening had become an incredibly important tool in the intelligence war. These recorded conversations produced a wealth of vital intelligence, from the Germans’ battle plans to the progress of Hitler’s secret weapons program that produced the V1 and V2 rockets. The listeners also recorded the first harrowing accounts of the Holocaust.

The Story in Numbers

Illustrations copyright Owen Freeman represented by Killington Arts